People have been eating oysters for thousands and thousands of years. Dishes like Chef Keller’s Island Creek Oysters and Pearls make it easy to forget that somewhere, many eons ago, some poor sod had to figure out how to open the damn things. Joe Neanderthal must have been pretty hungry to schlep the wife and kids out to the nearest oyster reef and start smashing shells open only to have to pick the gooey meat out of the rubble. This is probably the instance to which our oft-quoted friend Mr. Jonathan Swift referred; doubtless, the neighbors were talking. Somewhere along the line, however, someone clearly figured it out.

Indeed, a frequent highlight of archaeological sites worldwide are cyclopean mounds of oyster shells known as middens. The biggest contain millions and millions of shells (millions!), yet nowadays people award themselves a hearty pat on the back when they knock back twelve in a restaurant meal—that was a self-shucked midnight snack for a Shinnecock indian. Today, like so many manual skills, shucking has gone the way of the dodo and is once again the tallest hurdle for would be ostreaphiles to conquer. We continue to butcher our beloved bivalves despite the fact that we now have an array of elegant solutions at our disposal. It is the hope of this writer that with a little edification on the right tool for the job you, the reader, will go forth and shuck with alacrity—or at least purchase a good knife.

People often ask me what the best oyster knife is. You’ve probably realized by now that it wouldn’t be worth writing an entire blog post about this if there was a quick, easy answer. The overarching truth is that it really comes down to personal preference, but after shucking tens of thousands of oysters in my time on this planet I’ve at least developed a contemplative non-answer: “It depends on what kind of oyster you’re shucking.”

Indeed, the very best human tools are those designed and honed for one highly specified function—the samurai sword, the key, the tuning fork, the alpine ski. These are instruments with which one can practice their art or execute a task satisfactorily for an entire lifetime and only achieve perfection on the day when somebody hands them a better version.

I humbly submit that the oyster shucking knife deserves placement on that venerated list. Shucking an oyster is like picking the lock on a treasure chest—sure you could hurl it off a building and smash it open, but the delicate contents within would be ruined. By comparison, shucking a clam is a brutish act in which one pries the lid off said treasure chest—it does the job, but graceful it is not. Give oyster shucking its due and use the right knife. You wouldn’t open a bottle of wine with a hacksaw.

On any given night at Island Creek Oyster Bar there are as many as fifteen different types of oysters on the list, representing as many as five different species, from both coasts, Canada and the US. Looking behind the raw bar will not reveal one glinting steel knife—the ONE—rather, you’ll see a bucket full of eight or ten knives—a veritable quiver of arrows. Each of our magnificent shuckers has a favorite knife for each oyster, and this is how it should be.

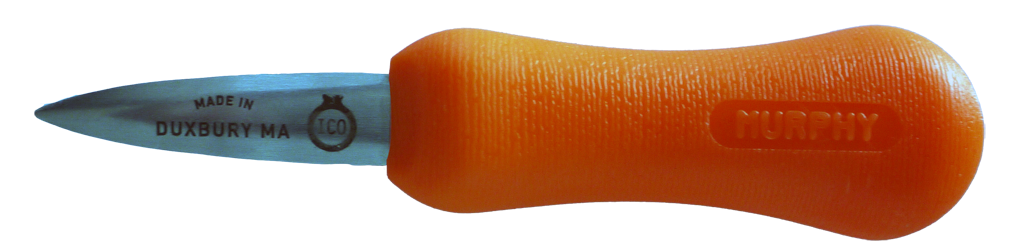

Working with an ancient knife and cutlery maker from the Western part of our state, we think we’ve developed the best perfect tool for shucking Island Creek oysters. It has a long, thick handle for grip. It has a full tang and high grade steel for torqueing. And most importantly it has a stout but sharp blade that comes to a point.

The point is key because it allows you to exert less force as you try to ease the knife between the two shells at the oyster’s hinge. In the event you screw things up, it may in fact be easier to inflict a small laceration with our sharp pointy knife, but given the immense amount of force required to insert a round, dull knife you’re much more likely to do serious damage. We’ll take the bandaid over a trip to the ER any day—its much cheaper. Not only that, but casually inserting the blade and nonchalantly tossing aside the top shell to reveal the pearly meat versus the inevitable grunting , groaning, and sweating that comes when you really have to put your weight into it is the difference between impressing your friends and making everyone feel awkward. Further, the blade is short because our oysters are not wide. It only has to be long enough to span the width of the oyster and cut the abductor muscle. Anything longer just elevates the center of gravity during the entry phase—not good.

Now, I would argue that the thing that makes Island Creeks unique (and the best) is not any one trait, rather it is the remarkable joining of many good traits in one beautiful little oyster. What this means for our knife is that its pretty versatile—the all mountain ski. It works well on almost any similarly sized oyster from Virginia to Prince Edward Island and even on some smaller West Coast oysters. That’s not to say, of course, that you won’t find a knife that’s better for a certain variety. Do not, however, attempt to shuck, say, a Gulf oyster with the ICO knife. You’re better off using a flathead screwdriver on those rocks.

Armed with the necessary knowledge and (once you complete checkout….wink) a masterpiece of a shucking knife, break free of the shackles of your Neanderthal past! Go forth and shuck!

–Chris Sherman runs marketing for Island Creek and is unfortunately better with a shucking knife than a pen.

Leave a Reply